July 17, 2025

Weekly Newsletter:

A Big Issue Covering Big Issues

We’re watching a national food policy spectacle play out in real time. Three highly anticipated announcements affecting all of food production will soon be released. Brands, organizations and advocates are tuned in and anxious to influence the pending policies. Adding to the tension is an administration enthusiastically pressing for a new “healthy” America, fomenting vigorous debate as it pits regulators and agencies against corporate interests, and cabinet members against each other.

- The Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) Commission’s comprehensive strategy, a follow-up to its assessment released in May, is expected next month.

- The 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans is rumored to be published by early fall.

- The FDA will define “ultra-processed” at some point in the unspecified future.

If the MAHA Commission is serious about achieving its goal of making America healthier — a worthwhile endeavor — it might consider talking to a farmer first.

Alexandra Dunn, President and CEO, CropLife America (The Wall Street Journal)

Making Food Production Manic

As dictated by a February executive order, the MAHA Commission published a 73-page assessment on May 22 as a first step to address childhood chronic disease. Relevant commission members include Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins and EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin. The assessment determined four “potential drivers behind the rise in chronic disease:” poor diet, environmental chemicals, lack of physical activity and “overmedicalization.”

To say the food production system — from agriculturalists and manufacturers to retailers and restaurants — reacted strongly to the assessment’s observations would be an understatement. While some groups commended the assessment’s focus on public health, most expressed concerns about its fuzzy scientific grounding, potential policy implications and the exclusion of key stakeholders in its development.

- Initial reactions from groups representing food manufacturers and agriculturalists proved vitriolic. American Farm Bureau Federation President Zippy Duvall said the assessment “sows seeds of doubt and fear about our food system and farming practices.” Jennifer Hatcher, chief public policy officer of FMI, The Food Industry Association, offered a more tempered statement: “We will advocate for realistic policies that are grounded in science, nutrition and consumer needs.” The Organic Trade Association remained introspective: “Unfortunately, the report’s recommendations do not yet address the urgent need for greater investment in organic.”

- Even the Center for Food Safety, a vocal critic of pesticides, complained: “The report then fails to address the policy and legal reforms necessary to stop this epidemic from continuing.”

- Sensing the industry’s frustration, the MAHA commission hosted a series of meetings at the White House to smooth things over. More than 50 food and agriculture industry groups, manufacturers (including Coca-Cola and PepsiCo), retailers (including H-E-B and Albertsons), and foodservice companies (including McDonald’s and GoTo Foods) met in small groups mid-June (Politico Pro, access required).

- On June 17, a group of 258 groups representing farmers, ranchers and manufacturers of food and ingredients issued a letter pleading for a seat at the table and accusing the report of lacking scientific rigor and transparency: “We are greatly troubled by the work of the MAHA Commission to date, which risks unnecessarily eroding public trust in our food supply.”

- CNN described (access required) further efforts undertaken to influence the commission, including the American Beverage Association stepping up its lobbying efforts.

- The Financial Times further described (access required) the industry’s “counteroffensive,” as well as some of the difficulties the commission’s strategy presents to manufacturers. “The food industry is coming to grips with the fact that the push for stringent regulation that was once a hallmark of liberal blue states is being embraced in the red ones.”

- Perhaps appealing to the Commission, major players in food production demonstrated efforts to comply. Kraft Heinz, General Mills, Nestle USA and Conagra all announced they will stop using certified food, drug & cosmetic colors. After meeting with Starbucks CEO Brian Niccol, Kennedy posted that Niccol “shared the company’s plans to further MAHA its menu.” And Steak ‘n Shake posted detailed plans to transition from seed oils in favor of butter and beef tallow.

What to expect:

- Most of the U.S. food system, at every point in the production chain, eagerly awaits release of the MAHA commission’s strategic plan, which is scheduled for release by Aug. 12.

- Agricultural groups, whose members largely supported the new administration in the 2024 election, are pressing hard for better inclusion in the strategic plan.

- No doubt, a new flurry of discussion, debate and contention awaits.

More Guidelines, More Problems

A key component of translating MAHA’s goals into practice is the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Since they affect purchase decisions for school foodservice, government agencies and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, aka food stamps), these guidelines carry a lot of weight.

Past recommendations have largely followed the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee’s scientific reports, the latest of which were published in December 2024. However, Trump administration officials are pushing for greater influence over this report, worrying food producers, processors, activists and nutritionists alike. In The Atlantic, writer Nicholas Florko captured (access required) their concern: “[RFK Jr.] mixes mainstream views with conspiracy theories. No one can predict exactly which of these views … will appear in four pages of dietary guidelines.”

- Prior to Kennedy’s novel approach, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee under the Biden Administration proposed the “Eat Healthy Your Way” dietary pattern as an “inclusive, flexible, dietary pattern that incorporates scientific evidence accumulated across many years.”

- In Food & Wine, Megan Meyer, PhD, explained what this looks like in practice: “Fruits and vegetables as dietary staples, whole grains over refined grains, low-fat dairy or fortified soy alternatives, vegetable oils in place of saturated fats, plant-based proteins as the primary source of protein.”

- The Meat Institute consolidated industry group complaints about protein-related recommendations, arguing: “Reducing animal-based protein foods will result in significant nutrient impacts.”

- The Institute of Food Technologists weighed in on language around ultra-processed foods, saying the category needs “a more nuanced approach to avoid restrictions on foods that could help people achieve a healthy diet.”

- Academics were split on the ultra-processed discussion. University of Minnesota nutrition professor Joanne Slavin, PhD, cautioned, “Let’s remember that processing is what allows for fortification with essential nutrients and gives us the ability to reduce sugar and sodium levels.” Meanwhile Tufts University nutrition professor Dariush Mozzaffarian, MD, DrPh, linked the category to adverse health outcomes.

- In a March update, Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins commented: “We will make certain the 2025-2030 Guidelines are based on sound science, not political science. Gone are the days where leftist ideologies guide public policy.”

- HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. concurred: “We are going to make sure the dietary guidelines will reflect the public interest and serve public health, rather than special interests.”

What to expect:

- The Trump administration estimates new dietary guidelines will be published sometime “early fall” or “before August,” depending which official is speaking (Reuters).

- Kennedy wants to simplify the guidelines to a mere four pages — 160 pages fewer than the 2020-2025 recommendations. While this may help the general public, such brevity could create ambiguity for those who prepare meals at an institutional scale. Expect challenges from industry groups if the guidelines shortchange nuance.

- Without delaying the process, the guidelines are unlikely to include ultra-processed food recommendations as neither the FDA nor USDA have officially defined the term; more on that below.

The public has mainly ignored past dietary guidelines.

Dan Flynn, Editor-in-Chief, Food Safety News

Ultra Ambiguous

Ambiguity around what, exactly, constitutes an ultra-processed food has thrown a wrench into policymaking for the MAHA commission and the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Academics and activists have outlined several definitions over the years, but the FDA has yet to commit to one. NYU professor emeritus and nutritionist Marion Nestle simplified the definition in an interview with Food & Environment Reporting Network: “To me, it’s junk food. It’s just a very defined category of junk food.”

Timing on an FDA recommendation for a definition is almost as murky as the definition itself. A June New York Times overview suggested to expect a draft in “the coming months,” while FDA commissioner Martin Makary told Food Safety News it would be more of a process, involving an industry roundtable. No matter what the FDA proposes, industry groups and activists will push hard for changes.

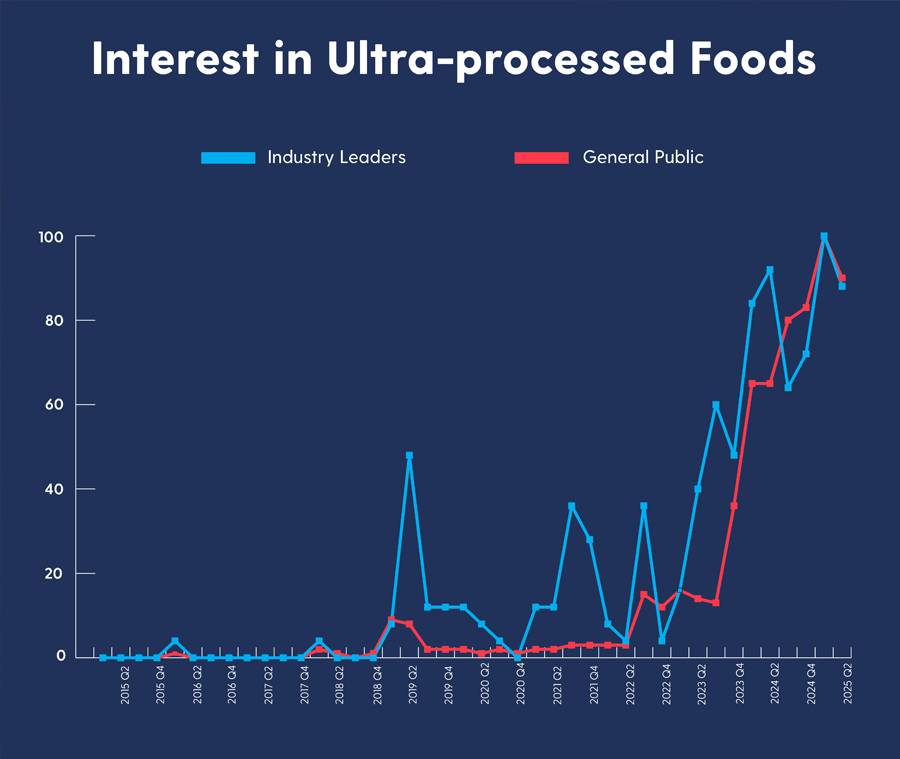

Although the term “ultra-processed” has been around for more than a decade, the first study to garner broad publicity came in 2019 (Cell Metabolism). Since that breakthrough study, the industry leaders that BR’s Intel Distillery follows (in blue above) have continued to mention the term — ramping up attention in early 2023. The general public (in red above) didn’t catch up until two quarters later. The Intel Distillery’s database is a leading indicator of the biggest food policy fights and an even better source for understanding the myriad interests at play.

Sources: Bader Rutter’s Intel Distillery and Google Trends

Sidebar: Regulatory Gerrymandering

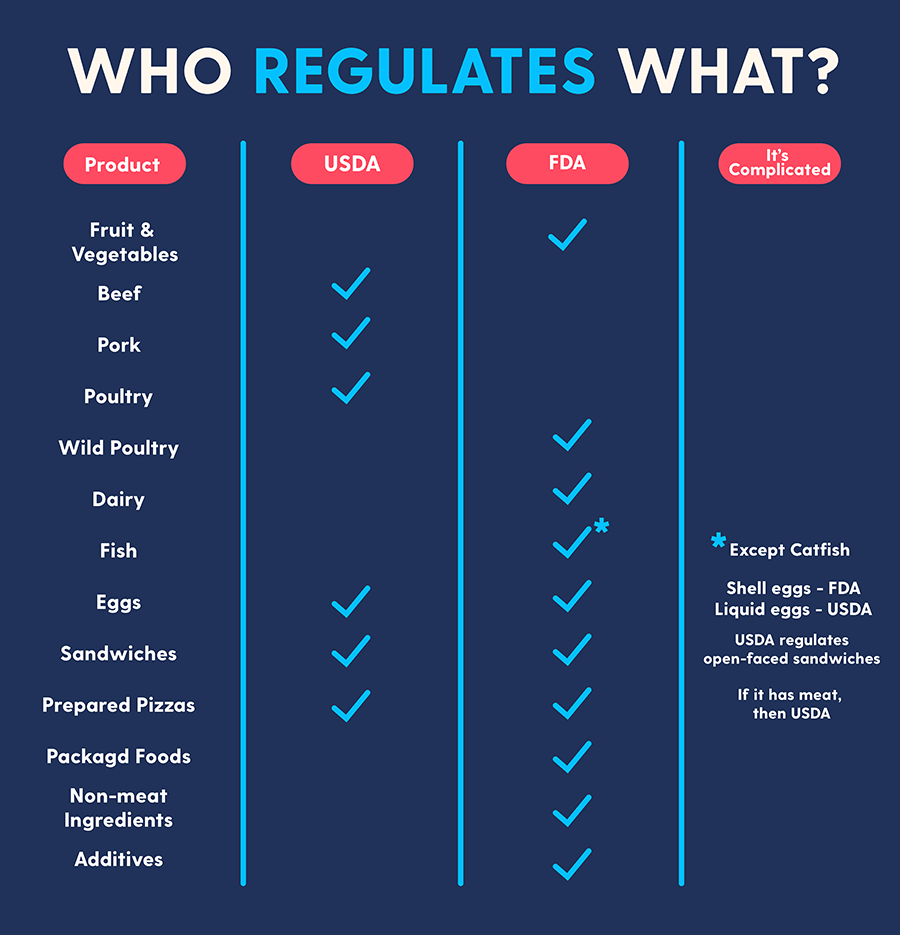

For all of its efforts to streamline government efficiency, the Trump administration has so far allowed the USDA and FDA to continue splitting food regulation jurisdiction. The occasionally arbitrary distribution of responsibilities has perplexed many for decades:

- Sen. Richard Durbin (D-Ill.) and other members of Congress have introduced bills to combine the agencies nearly every year since 2010

- Writers Michael Pollan and Mark Bittman advocated for consolidating the agencies’ goals as part of a “national food policy” in 2014.

- In 2023, Frank Yiannas, former FDA deputy commissioner, and Mindy Brashears, former USDA undersecretary for food safety, opined that the agencies should be under one roof.

Being curious food policy nerds, we dug in to see who regulates what. Somehow, we remain more confused than before we started down this path.

Midjourney illustration by Ryan Smith

Related Articles:

5 Realities Pressuring Foodservice

Weekly Newsletter | May 14, 2025

With the largest foodservice event in the Western Hemisphere happening in our own backyard, we fired up the Plated machine ...

Look! No Election Coverage!

Weekly Newsletter | November 7, 2024

Thank you for subscribing to Plated by Bader Rutter. What started as a weekly internal memo for keeping our agency ...

Plated Away From Home

Weekly Newsletter | October 31, 2024

The E. coli issue at McDonald’s (and Yum! Brands) goes on. Product development and menuing innovation carries on. Restaurant chain ...

Winds of Change

Weekly Newsletter | October 17, 2024

Hurricane relief and recovery efforts get on track. Dairy producers seek sustainability. Big manufacturers adapt strategy.

Skipping Meals & Fixing Prices

Weekly Newsletter | October 10, 2024

Industry and government tackled food prices, focusing on beef. Researchers, government and business got serious about obesity. Alternative proteins remain ...